THE BATTLE OF

THE ATLANTIC

Highlights from 422 R.C.A.F. Squadron, 1942 - 1945

The

early months of 1942 were not happy times for the Allied war effort. The attack

on Pearl Harbor in Dec., 1941, was soon followed by the loss of Hong Kong and

Singapore. A major part of the American and British naval strength had been sunk

in the Pacific and increased U-boat activity in the Atlantic was causing

devastating losses to the merchant shipping, so necessary for the transport of

fuel, food and other supplies to the U.K.

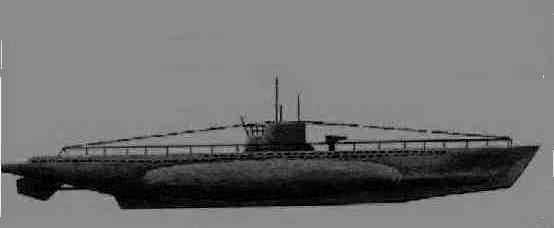

By early 1942

the enemy submarine  fleet

had grown to 250, of which nearly 100 were operational, and new additions were

being launched at a rate of 15 per month. At the same time, submarine activity

had become a problem on the Pacific coast of North America with large losses of

tankers coming from the Caribbean. Now almost two years old, the Commonwealth

Air Training Plan was providing an increased flow of aircrew for operational

duties. Initially a large percentage of graduates had been required for

instructional duties to meet the expanding training requirements; as the number

of graduates increased more and more proceeded overseas, most going to R.A.F.

units after operational training.

fleet

had grown to 250, of which nearly 100 were operational, and new additions were

being launched at a rate of 15 per month. At the same time, submarine activity

had become a problem on the Pacific coast of North America with large losses of

tankers coming from the Caribbean. Now almost two years old, the Commonwealth

Air Training Plan was providing an increased flow of aircrew for operational

duties. Initially a large percentage of graduates had been required for

instructional duties to meet the expanding training requirements; as the number

of graduates increased more and more proceeded overseas, most going to R.A.F.

units after operational training.

Early in the war, at both political and top military levels, discussions about the merits of having R.C.A.F. formations had resulted in an agreement in January, 1941 to form 25 R.C.A.F. squadrons in Britain by May, 1942. These would be in addition to the three squadrons that had been sent from Canada early in 1940.

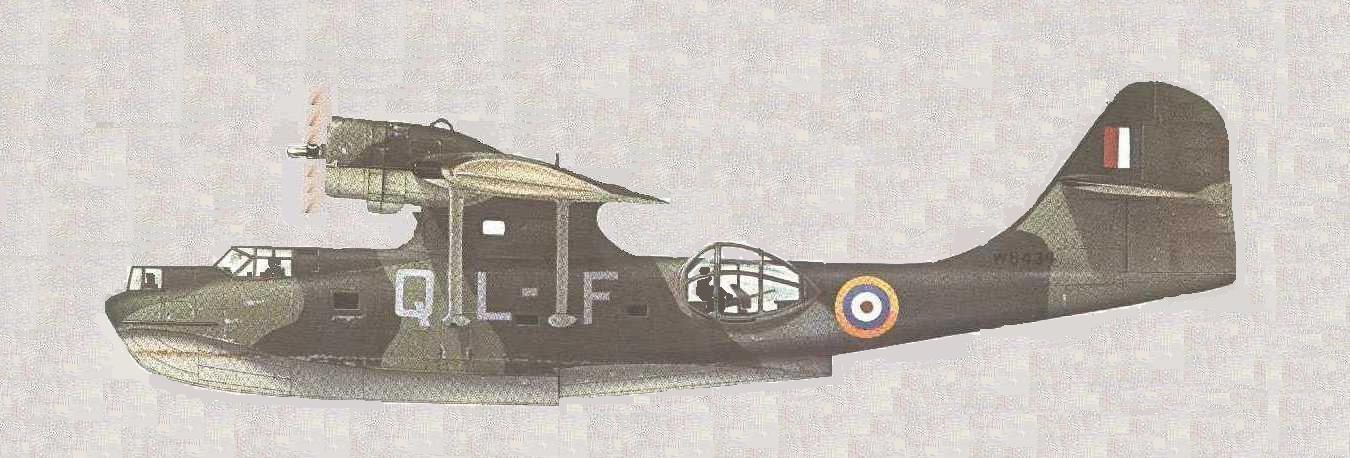

Twenty

squadrons had been formed in 1941, and on April 2, 1942, R.C.A.F. overseas

headquarters announced the planned addition of two flying-boat squadrons for

Coastal Command: #422 to be based at Lough Erne, Northern Ireland, with

Catalinas and #423 which would have Sunderlands and begin training at Oban in

Scotland. By May, 1942, the plans showed that #422 would have 9 Catalinas with

222 personnel. Records show that 13 ground staff arrived at Lough Erne June 3,

and when the first aircrew arrived on June 10 they found at least 50 airmen

already on the station. By the end of June, 200 personnel had been assigned to

the squadron, but without a C.O. or any aircraft. Some ground crew were

assisting with servicing of #230 (RAF) squadron aircraft and all remaining

personnel were organized into work parties for the task of building paths

through the mud that existed after the rapid construction during the short

period the base had been open.

On July 9, 1942, S/L L.W. Skey DFC arrived, having been appointed Commanding Officer on July 1. After graduating from the University of Toronto, local born Larry Skey, decided flying would be more interesting than finance. Thus, he took a course at the Toronto Flying Club. He received his commercial licence and then obtained passage to England in the summer of 1936. He joined the R.A.F. in September. When the war began he was a Sunderland pilot and in February, 1940, was awarded the DFC for his duties, which included operations into Norway. Also, on July 8, 1942, F/L Roger Hunter DFC, an experienced R.A.F Catalina pilot, arrived to be flight commander.

The squadron was still without aircraft, as most of the production of Catalinas

was required to bolster the North American coastal defences. The few delivered

to England were needed to keep the RAF squadrons at full strength.

Skey,

therefore, arranged  for

seven Saro Lerwicks, which were being little used at the Invergordon, Scotland,

OTU, to come to Lough Erne to allow some training while awaiting the Catalinas.

The twin engine Lerwicks, no longer in production, had been withdrawn from

operational service the previous year by the R.A.F.

for

seven Saro Lerwicks, which were being little used at the Invergordon, Scotland,

OTU, to come to Lough Erne to allow some training while awaiting the Catalinas.

The twin engine Lerwicks, no longer in production, had been withdrawn from

operational service the previous year by the R.A.F.

Early in August, the squadron received three Catalinas. In mid August two of

these were flown to Vaagar in the Faroe Islands to assist in the calibration of

the recently installed DF equipment. At Lough Erne training continued with the

aircraft available, but the frequently unserviceable Lerwicks kept this to an

undesirable minimum. Then, late in August, the three Catalinas, with their crews

and Flight Commander Hunter, were dispatched via Invergordon and Sullom Voe in

the Shetland Islands, Scotland, to Lake Lachta near Archangel and to Graznya

near Murmansk in northern Russia. Their task was to carry out anti-sub patrols

and to transport men and equipment, required for new wireless installations, to

be used in protecting convoys carrying much needed supplies to Russia.. The

aircraft and crews were all back at Lough Erne by Sept. 24, 1942.

By this time, a number of Catalinas were available for overseas so Larry Skey

arranged for eleven skeleton crews to travel to Canada to ferry the aircraft to

the U.K. They departed on the Queen Mary on Oct. 7, sailing to Boston and then

traveled by train to Montreal. Following a week of leave for the RAF members and

two weeks for the Canadians, the eleven aircraft carrying spare parts, freight

and aluminum ingots were delivered via Gander Lake, the last arriving at

Greenoch, Scotland,

November 8, 1942.

As this was happening, the squadron moved to Oban Nov. 6 for conversion to

Sunderlands. 423 squadron, now operational, moved with their Sunderlands to

Lough Erne. The ferried Catalinas would be used by others. Through the winter,

conversion training continued and on March 1, 1943,

the squadron was considered operational. During this time a number of the RAF

pilots were posted to RAF squadrons and replaced by Canadians now coming from

the OTU at Invergordon.

Another new member was a black cocker spaniel which received the name "Dinghy" and became the pet of the squadron medical officer, F/L Arnold Jones. In April, the flight commander, S/L Hunter, was posted to Pensacola, Florida.

Early in May, 1943, #422 squadron moved to Bowmore on the Isle of Islay,

Scotland, with most of the ground crew and equipment carried by 5 naval landing

craft. Here the squadron acquired three more aircraft, left by #246 (R.A.F.)

squadron as well as a new flight commander, S/L Brian Young. With no slip at

Bowmore, much of the maintenance was carried out at Wig Bay and many of the #422

ground crew were stationed there until the squadron move to Castle Archdale on

Lough Erne.

Patrols in the Atlantic and the Bay of Biscay commenced immediately, many of

these flown from Lough Erne in N. Ireland because it was closer to the patrol

areas. Late in May, the first operational casualties occurred when Frank Paige

and his crew were lost at Clare Island on the west coast of Ireland while

returning to Lough Erne from an Atlantic patrol.

During the next few months, many new crews and ground crew arrived and the

Canadian RCAF content of #422, which had been about 33% a year earlier, reached

more than 75%. Patrols continued with a few U-boat sightings but no attacks. On

September 3, following the loss of two engines, Jacques de le Paulle ditched his

Sunderland in the Bay of Biscay and the crew successfully boarded their

dinghies. On Sept. 6, the dinghies were spotted by a U.S navy Liberator. A

Sunderland of #228 squadron was homed to the scene, landed and after a scary

take-off in the moderate swells, carried the crew to Pembroke Dock, Wales.

Later that month, September 28, 1943, Sunderland J was lost when the skipper, George Holley, attempted to land on the water near Rekjavik, Iceland, in foggy weather, but the crew members were all safe. Back at Bowmore, the gale season had begun in September and continued into October. Gale crews were frequently suffering the misery of rough seas to protect the aircraft.

On October 17, 1943, Paul Sargent and crew, on patrol well out in the Atlantic

south of Iceland, encountered two U-boats side by side on the surface and made

an attack which was unsuccessful. A second determined attack was made with

little evasive action under heavy enemy fire. The

depth charges dropped close to the target but the aircraft was severely damaged

and three of the crew were killed by the U-boat guns. The aircraft was flown to

a nearby convoy and ditched, in heavy seas, alongside H.M.S. Drury, one of the

escorts. Unfortunately, Sargent was trapped in the wreckage and went down with

his craft. The remainder of the crew were rescued and carried to St. Johns,

Newfoundland, where three of the crew were hospitalized. This attack occurred

during one of the largest convoy battles of the war with large escort forces and

many Coastal Command aircraft participating. Five U-boats were probably sunk and

others damaged.

October 27, 1943 saw the handing over of the squadron, from Larry Skey, to the

new Commanding Officer, W/C Joe Frizzle. On Nov. 1, the squadron moved its

operations to Castle Archdale in N. Ireland, the ground crew again traveling by

Navy landing craft from Bowmore to Londonderry and

then by train to Enniskillen. At the time, Castle Archdale had two other

squadrons at the base and with insufficient accommodation most of #422 were

housed in the barracks at St. Angelo, some seven miles distant. On the 20th of

November, 1943, to protect a convoy taking supplies to the

forces in Italy, three aircraft were dispatched; one from #423 and two from #422

squadron with orders to land at Gibraltar in order to extend the patrol time

around the convoy. One aircraft, with skipper Dave Ulrichsen, sent a sub

sighting report at 17:40. Later an S.O.S. was received but the aircraft and

eleven crew members were lost.

In December, a blockade runner had been located trying to reach a port in

France. On the 27th, aircraft were dispatched to follow and destroy the vessel.

Bill Martin and crew, aboard Sunderland Q of 422, which was armed with 500 pound

bombs in lieu of the normal depth charges, located

and followed the ship. Before leaving they attempted to drop the bombs on the

vessel, a most difficult task as the aircraft was not equipped with a bomb

aiming device.

The first few months of 1944 saw the posting of S/L Brian Young, adjutant Bill

Murphy and a number of the skippers who had by then completed their operational

tours. During this time, some of the experienced second pilots were given extra

training to take over from the departing skippers, as their crews had not yet

completed their required 800 hours of operational time.

Also, early in the year the squadron mascot "Dinghy" became the parent of a litter; one of these was donated to 422, received the name "Straddle" and after "Doc" Jones was posted in March, "Straddle" became the new mascot and the responsibility of F/O Lloyd Detwiller.

March 10, 1944 brought the squadron's first confirmed sinking of a U-boat when

Frank Morton and crew, having recently arrived from OTU, were on patrol being

screened by F/L Sid Butler. With Sid at the controls, an excellent attack was

made with depth charges straddling the sub and shortly thereafter, the U-boat

sailors were boarding their dinghies. The aircraft returned to Castle Archdale

with a superb set of photos of the attack and of the sailors in their dinghies.

Early in April,

#201 (R.A.F.) squadron moved to Pembroke Dock from Ireland, and #422 was then

able to take over their quarters at Castle Archdale. The move brought the

convenience of being closer to the aircraft and operationalfacilities but was

also notable in the decrease in the quality of meals. By then, activity in the

Atlantic had decreased as the enemy forces were being withdrawn in anticipation

of the expected invasion. The squadron increased training and leaves were

canceled for the ground crew to ensure every aircraft would be serviceable for

the forthcoming activity.

By mid May, 1944, Coastal Command had detected increased U-boat movements along

the Norwegian coast and to provide added patrol strength for 18 Group aircraft

and crews from #422 and #423 squadron were detached to Sullom Voe in the

Shetlands. Also, RCAF Squadron #162, with their Cansos, was transferred from

Iceland to a base in northern Scotland. On May 24, 1944, the #422 crew,

skippered by George Holley, left Sullom Voe at 0800 hours for a patrol off the

Norwegian coast. Later, at 1419, an S.O.S. was received by a nearby #423

Sunderland. A moment later the crew of that aircraft noticed a large splash in

the distance, turned to investigate and a few minutes later sighted the wake of

a U-boat. An attack was made but the U-boat was able to submerge when the depth

charges fell short. On the approach to attack, the crew of the #423 aircraft

noted some wreckage and later returned to investigate. This, apparently, was the

remains of Holley's aircraft. There were no survivors.

#422 and #423 squadrons remained busy patrolling from the Shetland base until

D-day. During May and early June, Coastal Command aircraft and Navy activity

along the Norwegian coast resulted in at least eleven subs sunk. Then on June 6,

the squadrons were ordered to return all aircraft to Castle Archdale. All leave

was then cancelled.

Coastal Command had the task, along with the Navy, to protect the flanks of the invasion forces that began to cross the Channel on D-day, June 6, 1944. The plans called for coverage of the area in the Channel, westward from the Cherbourg peninsula to all the ocean area between south-east Ireland and France, so that the whole area was patrolled at least every thirty minutes night and day. #422 and #423 were required to support #19 Group in this task with three or four aircraft.. For the next two months this was the major activity, but the Atlantic patrols continued.

July 1 was celebrated with a party hosted by W/C Frizzle and the squadron

officers for the hard working ground crew who had been without leave for some

months to ensure all aircraft were in good shape for the invasion. Late in the

month, leave was restored but travel was not allowed to England or Scotland. The

summer of 1944 saw the U-boats now equipped with their shnorkels

coming close to the shores of Ireland and Britain. Often remaining hidden during

daylight hours, they looked for passing steamers at night.

For a short

time, many squadrons were not equipped for night attacks. During this period 422

aircraft engaged in dropping four minute parachute flares throughout the hours

of darkness off the north coast of Ireland. All depth charges had been removed

to allow for the weight of the flares and it was strenuous exercise for the crew

members detailed to handle the flares every four minutes throughout the night.

The aircraft, without depth charges, could not attack but hopefully the lighting

of the skies would deter movements by the U-boats.

August 12, 1944

saw the crash of Sunderland T of 422, in Donegal County, Ireland, just north of

Belleek, Northern Ireland, shortly after take-off for an Atlantic patrol. The

heavily loaded aircraft had sufferred an engine fire and loss of propeller and a

crash landing was attempted on a relatively flat area. The skipper, F/L Cam

Devine and two crew members died in the crash. The remainder of the crew

received serious injuries and were initially treated in the Irish hospital in

Ballyshannon, Donegal County, and later moved to the military hospital in

Necarne Castle near Irvinestown, Northern Ireland or to hospitals in England.

At the end of

October, 1944, W/C Jack Sumner took over command from W/C Joe Frizzle, and the

move of #422 to Pembroke Dock in Wales was announced, replacing #201 squadron

who were returning to Castle Archdale. Most ground crew left by rail from

Irvinestown on Nov. 3 for Larne, by ferry to Stranraer and then overnight by

train to Pembroke Dock. The aircraft and remainder of the squadron, delayed a

few days because of foul weather, arrived on Nov. 7 at their new base, also home

to #228 (RAF) and #461 (RAAF) squadrons.

Here were new

surroundings for #422. Accommodation for much of the squadron was in permanent

buildings that had, in peace time, been married quarters. However, although the

accommodation was a great improvement over Nissen huts, the short supply of coal

for heating and the exceptional cold of the 1944/45 winter months made for many

uncomfortable nights.

The aircraft were now on salt water and the very strong tides added a new

challenge for crews when mooring. The station was adjacent to the town of

Pembroke Dock, a pleasure for off-hours. Intensive training and very poor

weather reduced operational sorties to a minimum until the latter half of

December. A highlight, of that month, was a squadron party on Dec. 26 much

enhanced by supplies of turkey, other food and beverages obtained during a

special flight to Castle Archdale.

Poor weather continued through January, 1945. A gale with winds to 100 knots on the 18th resulting in much damage to marine craft and the loss of one #228 and three #461 Sunderlands; #422 was fortunate that all their aircraft survived the storm. Then from the 24th to 27th snow shut down all operations. It was one of the worst winters in years, an event that was also creating great delays in the advance toward the Rhine by the allied armies. When the weather was acceptable, patrols were carried out and training continued but this was minimal in Febraury when weather conditions cancelled all flying on 14 days and allowed only very limited operations on at least 5 more. However, by early March most crews had completed their training exercises with the sonobuoys and they soon proved their worth when sightings and attacks were made by five crews by the end of March.

March, 1945 also saw the opening of Canada House, a five room hall at the rear of Trinity church in Pembroke Dock. This became a recreation area for all ranks of #422 squadron with a small library, reading and writing rooms and a snack bar in the main room which had been decorated by ten airmen volunteers. A squadron dance band had been formed, following the acquisition of musical instruments from K.of C. Services. Later a bugle band was also formed with F/O Al Platsko, who had returned to the squadron after recovering from injuries received in the crash with Cam Devine the previous August, in charge. A news sheet, the "Short Slip", begun earlier in the year, was now being published on a regular basis. Social life included frequent squadron dances; in April the softball season opened and canvassing began for another Victory Loan campaign. May 8, V-E day, began with a service in the station church, a ball game in the afternoon and two large dances in the evening. Operational patrols continued, to ensure all U-boats accepted the surrender rules.

On May 24, 1945 a third anniversary celebration included a squadron inspection,

a march past in the town square, sports in the afternoon and a dance in the

evening. By the end of the month, rumours of change for the squadron abounded

and on June 1, #422 was attached to Transport Command. That day, in a final

Coastal Command gesture three squadron Sunderlands were flown in formation to

circle the passenger ship "Louis Pasteur" enroute to Canada with Canadian airmen

to give them a proper send off.

By mid June, 1945, many of the RAF members of the squadron had been posted and some Canadians were on there way home. In late June most of the Sunderlands were flown to Castle Archdale for disposal with the last departing on July 2. The remainder of the squadron departed by train for Bassingbourne July 24 for training on Liberators for transport duties in the Far East. Training continued until August 27, then all flying stopped.

September 3,

1945 brought the final word - #422 was to be disbanded and it was time to head

home.

The

squadron had served with Coastal Command from the summer of 1942 to the summer

of 1945, patrolling the oceans from bases in Scotland, Northern Ireland and

Wales, northward from the Shetland Islands, off the coast of Norway and as far

as Murmansk in northern Russia, westward to Rekjavik in Iceland and beyond

to 30 degrees west, southward over the Bay of Biscay and as far as Gibraltar,

and after D-day over the Channel and its approaches as far east as the Channel

Islands to protect the Allied invading forces. When hostilities ended, most

squadron members went home; but some remain, at rest, in cemeteries in Scotland,

Northern Ireland, Wales, England and Norway; more lie with their aircraft deep

in the sea.

We will always

remember them!

(For the names of

1,200 members in #422 squadron WWII and some of their personal stories, link to

www.georgian.net/422sqdrn )

DF

Direction Finding (ultra high frequency)

DFC

Distinguished Flying Cross

OTU

Operational Training Unit

Schnorkel

- tubes extending above the surface from a U-boat, enabling it

to run on Diesel engines while submerged

Sonobuoy

- A device released from aircraft, which converted sound waves

to an electromagnetic signal, received in aircraft to detect U-boats.

SOS

An urgent Morse Code signal call for help. (easy to send and

receive and rumoured to originally mean "Save Our Souls").